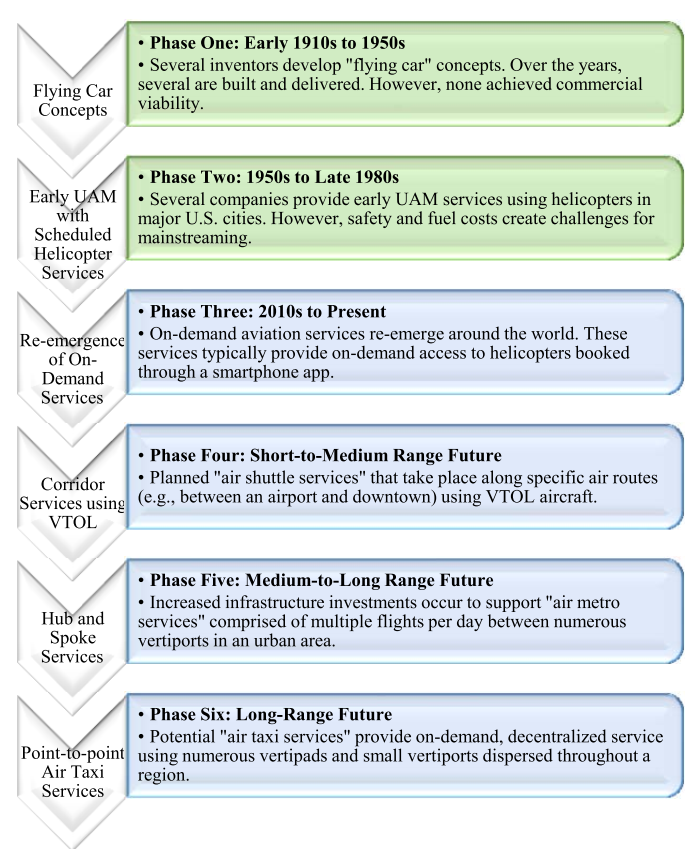

The concept of urban aviation is not new. Beginning in the early 1900s, inventors began developing “flying car” concepts and by the mid-20th century, early operators began offering scheduled flights using helicopters. The history of UAM's might be described in the two initial phases.

History of Urban Air Mobility

Flying Car Concepts

The concept of UAM traces its origins to the Autoplane, a functional “flying car” developed by Glenn Curtiss around 1917. Over the years, automakers and inventors built and delivered various concepts for flying automobiles. In the 1920s, Henry Ford developed a concept for “plane cars” and began developing single-seat aircraft prototypes. Ford’s flying car project ended within a few years following a crash and fatality of their test pilot. In 1937, Waldo Waterman developed the Arrowbile, a hybrid Studebakeraircraft with detachable wings, but the project dissolved due to a lack of funding. The 1940s was marked by several efforts including the first “flying car” to be approved by the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA), the predecessor to the FAA, the Airphibian. Despite the aircraft’s technical achievements, it never received investment capital. Inspired by the Airphibian, Moulton “Molt” Taylor developed the Aerocar prototype in 1949. The flying car was the second and last roadable (i.e., aircraft that can be driven on roadways as vehicles) aircraft to receive CAA approval. Consolidated-Vultee developed the ConvAirCar in 1947, a two-door sedan equipped with a detachable airplane unit. However, the project ended after a crash on its third test flight. In the late 1950s, Ford developed the Levacar Mach I, a vehicle prototype suspended just slightly above the surface by ducted air from three levapads on its underside. The first early VTOL aircraft designed for military use, the Avrocar, was initially funded by the Canadian government but was dropped when it became too expensive. In 1958, the U.S. Army and Air Force took over the project. However, this flying-saucer-shaped aircraft suffered from thrust and stability problems and the project was canceled in 1961. None of these early concepts achieved commercial viability.

Although inventors, engineers, industrial designers, and technology entrepreneurs have long envisioned a future of “flying cars,” there were a number of technical and practical factors that have made this difficult to achieve. As a practical matter, the addition of wings to a traditional vehicle chassis can block driver sight lines and make a vehicle difficult to drive and park on roadways. Because the size, shape, and weight distribution needs are very different between vehicles and aircraft, both have very different regulatory, technical, and safety design considerations that make it difficult to design one vehicle/aircraft that can serve both use cases (e.g., aircraft engines have been designed to take advantage of air cooling whereas car engines are designed to be water cooled to prevent overheating while in traffic). Although there has been a lot of experimentation with flying car concepts, these longstanding practical and technical challenges caused the industry to focus more on improving safety and enhancing economic and operational efficiency of vertical flight.

Early UAM Operations With Scheduled Helicopter Services

Between the 1950s and 1980s, several operators began providing early UAM services using helicopters in Los Angeles, New York City, San Francisco (SF Bay Area), and other cities. New York Airways offered passenger service between Manhattan and LaGuardia in the mid-1950s. In the U.S., these early passenger helicopter services were typically enabled through a combination of helicopter subsidies (discontinued in 1966) and airmail revenue. Between 1965 and 1968 (resuming in 1977), Pan Am offered hourly connections between Midtown and JFK’s WorldPort, allowing passengers to check in at the Pan American building in Midtown 40 minutes prior to their flight departure at JFK. Over the years, the service offered various promotions, such as “buy one, get one free” that offered international business travelers a free helicopter connection to their flight. The service was discontinued in 1977 when an incident involving metal fatigue of the landing gear caused a rooftop crash killing five people (four people on the roof and one person 59 stories below on the ground).

Helicopter services began to slowly re-emerge in Manhattan in the 1980s. Trump Air offered scheduled service using Sikorsky S-61 helicopters between Wall Street and LaGuardia airport connecting to Trump Shuttle flights. The service was discontinued in the early 1990s when Trump Shuttle was acquired by US Airways. Inventors continued developing flying car and VTOL prototypes during the 1960s and 1970s. Engineer Paul Moller began developing VTOL aircraft in the 1960s, and an early prototype hovered a few feet off of the ground in 1967. The 1966 Aerocar was able to reach 60 miles per hour (mph) on the ground and 110 mph in the air. Advanced Vehicle Engineers (AVE) created a flying car by combining a Cessna Skymaster and a Ford Pinto; however, a test flight crash ended the project in 1973. The 1980s also saw several attempts to develop new VTOL aircraft. Boeing invested $6 million US into the Sky Commuter program and developed three VTOL prototypes before the program was canceled. Moller developed the M200X in 1989. The flying-saucershaped aircraft reached an altitude of 40 feet and remained irborne for three minutes. The project evolved into the Moller Skycar, which was under development until 2003.

Summary

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike License 4.0