The Department of Justice defines credible threat as the reasonable belief based on the totality of circumstances that the activity of a UAV or UAS may, if unabated:

- Cause physical harm to aperson;

- Damage property, assets, facilities, or systems;

- Interfere with the mission of a covered facilityor asset, including its movement, security, or protection;

- Facilitate or constitute unlawfulactivity;

- Interfere with the preparation or execution of an authorized government activity, including the authorized movement of persons;

- Result in unauthorized surveillance or reconnaissance; or

- Result in unauthorized access to or disclosure of classified, sensitive, or other wise lawfully protected information.

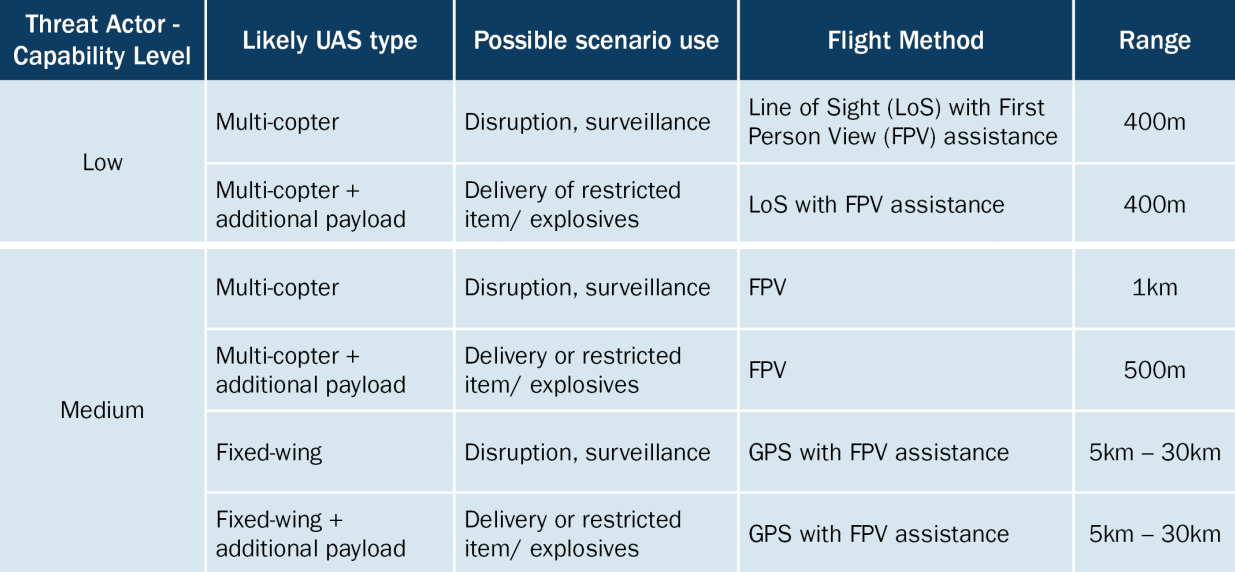

Many UAS events are caused by careless or reckless operators. An adversary can also use UAS in a variety of malicious ways, which include the following:

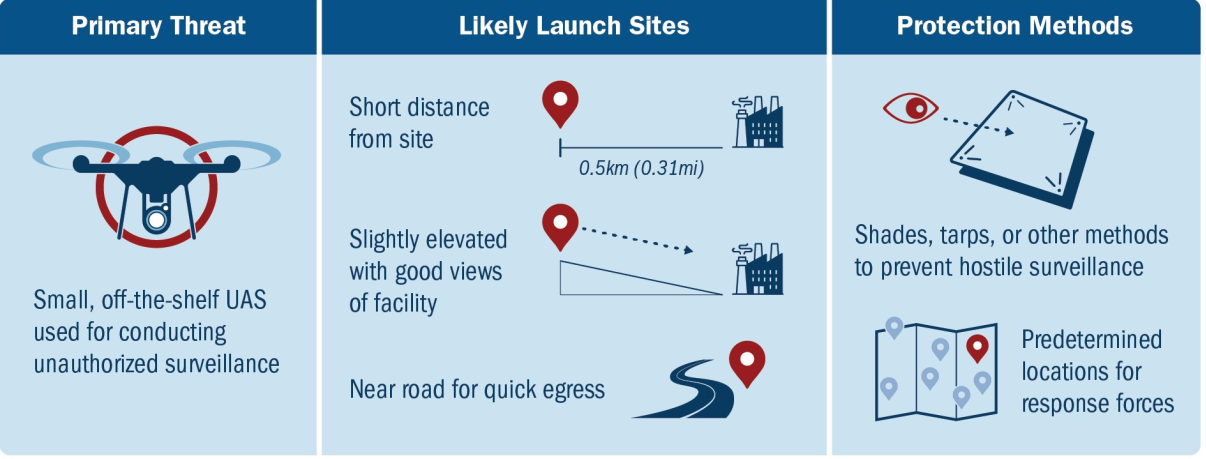

- Hostile Surveillance. An adversary uses UAS to collect information about federal government operations, security measures, or law enforcement operations.

- Smuggling or Contraband Delivery. An adversary uses UAS to bypass security measures to deliver illegal or prohibited items onto federal property.

- Disruption of Government Business. An adversary uses UAS to interfere with federal government operations through the presence of the UAS, use of on-board cyber-capabilities, or by using the UAS to distribute propaganda onto federal property.

- Weaponization. An adversary mounts a firearm, explosive, chemical, or biological agent on a UAV or deliberately crashes the UAV in an attack.

Examples of UAS as a Threat

Example of Mitigating UAS Threat

Drones can be used to attack critical infrastructure in a number of ways, all of which challenge the prevailing security model of securing the ground plane. Drone threats include:

Surveillance. The most basic risk is the potential for one or more UAVs to loiter outside a critical perimeter in an ISR role, capturing sensitive information, which could range from raw materials delivery, to shift changes, parking lot counts, security patrol schedules, or other activities. This information gathering poses a fundamental security risk but may also be a precursor to further escalations and attacks once targets are identified and security capabilities mapped out. Sensors and systems that can easily identify persistent hovering drones over a large secure perimeter are a key piece of the air security puzzle.

Perimeter Intrusion. Crossing a fence line or secure perimeter to enter a facility’s airspace is an escalation that needs to be carefully monitored and potentially mitigated subject to prevailing legal authorization. While an accidental or clueless overflight may happen on occasion, this could represent a criminal act that needs a fully documented evidence trail. The 2018 Greenpeace stunt in which a Superman-shaped drone was crashed into a French nuclear plant to demonstrate its vulnerability to outside attacks is an example of such an intrusion. Sensor solutions such as radar that provide precise time-stamped geo-location provide critical evidence for prosecution.

Extended Cyber Attack Surface. Landing unobserved in remote locations to probe wireless networks for weaknesses is real. Industrial facilities in remote locations with a robust 2D security perimeter may have less security for network and systems access – after all, the threat of an inexpensive drone with cyber capabilities was science fiction just a few years ago. It’s very real today. Extending the cyber perimeter requires sensor capabilities similar to surveillance needs.

Infrastructure Damage. Beyond simple trespass, flying a UAV over traditional perimeters, such as a fence, and kinetically impacting critical infrastructure is a low effort approach that garners headlines. One might assume the small mass and velocity of a UAV may not by itself pose a significant threat to a hardened facility. In 2017, a Silicon Valley man triggered a power outage impacting 1,600 people when he crashed his drone into a Mountain View high-voltage wire and caused tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of damage. The ability to configure these precision UAV platforms to deliver payloads to an exact location is a huge risk to power plants, substations and datacenters where outages can cost millions of dollars per hour. Sensors that can track and highlight air targets flying towards these particularly vulnerable areas offer critical situational awareness and time to react.

Explosive Delivery. Finally, the potential for explosive payloads to be carried by these drone platforms and precisely delivered to weak points is an inevitable risk that needs to be discussed in the context of critical infrastructure. While even the popular Phantom4 UAV can be modified to carry a couple grenades as demonstrated by ISIS in the Middle East, the greater threat are the larger payload platforms that can deliver 5 kgs of improvised munitions into a chemical plant, refinery or similar target where they’re most vulnerable. High risk locations must have sensors that can detect, track, and identify objects of interest in the airspace with sufficient advanced warning time to trigger precision interdiction.